What if the World Had to Use Horses Again

A number of hypotheses exist on many of the central issues regarding the domestication of the equus caballus. Although horses appeared in Paleolithic cave art every bit early on as 30,000 BCE, these were wild horses and were probably hunted for meat.

How and when horses became domesticated is disputed. The clearest evidence of early on use of the equus caballus as a means of transport is from chariot burials dated c. 2000 BCE. Still, an increasing amount of evidence supports the hypothesis that horses were domesticated in the Eurasian Steppes approximately 3500 BCE;[1] [2] [3] recent discoveries in the context of the Botai culture advise that Botai settlements in the Akmola Province of Kazakhstan are the location of the primeval domestication of the horse.[4]

Use of horses spread across Eurasia for transportation, agricultural work, and warfare.

Background [edit]

The date of the domestication of the horse depends to some degree upon the definition of "domestication". Some zoologists define "domestication" equally human control over breeding, which can exist detected in ancient skeletal samples past changes in the size and variability of ancient equus caballus populations. Other researchers look at the broader evidence, including skeletal and dental evidence of working activity; weapons, art, and spiritual artifacts; and lifestyle patterns of human cultures. There is also bear witness that horses were kept as meat animals before they were trained every bit working animals.[ commendation needed ]

Attempts to date domestication past genetic report or analysis of physical remains rests on the assumption that at that place was a separation of the genotypes of domesticated and wild populations. Such a separation appears to have taken place, but dates based on such methods can only produce an judge of the latest possible engagement for domestication without excluding the possibility of an unknown period of before gene flow betwixt wild and domestic populations (which will occur naturally as long equally the domesticated population is kept within the habitat of the wild population). Farther, all modernistic horse populations retain the ability to revert to a feral state, and all feral horses are of domestic types; that is, they descend from ancestors that escaped from captivity.[ commendation needed ]

Whether one adopts the narrower zoological definition of domestication or the broader cultural definition that rests on an array of zoological and archaeological prove affects the fourth dimension frame chosen for the domestication of the horse. The engagement of 4000 BCE is based on testify that includes the appearance of dental pathologies associated with bitting, changes in butchering practices, changes in man economies and settlement patterns, the depiction of horses equally symbols of power in artifacts, and the appearance of horse bones in human graves.[5] On the other hand, measurable changes in size and increases in variability associated with domestication occurred subsequently, near 2500–2000 BCE, as seen in horse remains found at the site of Csepel-Haros in Hungary, a settlement of the Bell Beaker civilisation.[6]

Use of horses spread across Eurasia for transportation, agricultural work and warfare. Horses and mules in agriculture used a breastplate blazon harness or a yoke more suitable for oxen, which was not as efficient at utilizing the total forcefulness of the animals as the later-invented padded horse collar that arose several millennia later.[7] [8]

Predecessors to the domestic horse [edit]

Replica of a horse painting from a cave in Lascaux

A 2005 study analyzed the mitochondrial Dna (mtDNA) of a worldwide range of equids, from 53,000-year-old fossils to contemporary horses.[9] Their analysis placed all equids into a unmarried clade, or grouping with a unmarried mutual ancestor, consisting of three genetically divergent species: the South American Hippidion, the Due north American New World stilt-legged horse, and equus, the true horse. The true horse included prehistoric horses and the Przewalski'due south horse, as well as what is at present the modern domestic horse, belonged to a unmarried Holarctic species. The true horse migrated from the Americas to Eurasia via Beringia, becoming broadly distributed from North America to cardinal Europe, northward and south of Pleistocene ice sheets.[9] Information technology became extinct in Beringia around xiv,200 years ago, and in the rest of the Americas around 10,000 years ago.[10] [11] This clade survived in Eurasia, however, and information technology is from these horses which all domestic horses appear to have descended.[9] These horses showed niggling phylogeographic structure, probably reflecting their loftier degree of mobility and adaptability.[9]

Therefore, the domestic equus caballus today is classified as Equus ferus caballus. No genetic originals of native wild horses currently be. The Przewalski diverged from the modern horse before domestication. It has 66 chromosomes, as opposed to 64 amid mod domesticated horses, and their Mitochondrial Dna (mtDNA) forms a distinct cluster.[12] Genetic evidence suggests that modern Przewalski's horses are descended from a distinct regional gene pool in the eastern part of the Eurasian steppes, non from the same genetic group that gave rise to modern domesticated horses.[12] However, evidence such every bit the cave paintings of Lascaux suggests that the ancient wild horses that some researchers now label the "Tarpan subtype" probably resembled Przewalski horses in their general advent: big heads, dun coloration, thick necks, stiff upright manes, and relatively brusk, stout legs.[thirteen]

Equus caballus germanicus front leg, teeth and upper jaw at the Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin

The horses of the Water ice Age were hunted for meat in Europe and beyond the Eurasian steppes and in Due north America by early modern humans. Numerous kill sites exist and many cave paintings in Europe point what they looked like.[14] Many of these Ice Historic period subspecies died out during the rapid climate changes associated with the end of the last Water ice Historic period or were hunted out by humans, specially in North America, where the horse became completely extinct.[15]

Classification based on body types and conformation, absent the availability of Deoxyribonucleic acid for enquiry, once suggested that there were roughly 4 basic wild prototypes, thought to accept developed with adaptations to their surroundings before domestication. There were competing theories: some argued that the 4 prototypes were dissever species or subspecies, while others suggested that the prototypes were physically different manifestations of the same species.[13] However, more recent study indicates that there was only ane wild species and all different body types were entirely a upshot of selective breeding or landrace accommodation after domestication. Either way, the most common theories of prototypes from which all modern breeds are idea to have developed suggests that in improver to the so-called Tarpan subtype, at that place were the following base of operations prototypes:[13]

- The "Warmblood subspecies" or "Forest Equus caballus" (once proposed as Equus ferus silvaticus, likewise known as the Diluvial Horse), which evolved into a later variety sometimes called Equus ferus germanicus. This prototype may have contributed to the evolution of the warmblood horses of northern Europe, also equally older "heavy horses" such every bit the Ardennais.

- The "Typhoon" subspecies, a small, sturdy, heavyset animal with a heavy hair coat, arising in northern Europe, adjusted to common cold, damp climates, somewhat resembling today's draft horse and even the Shetland pony.

- The "Oriental" subspecies (in one case proposed as Equus agilis), a taller, slim, refined and agile creature arising in Southwest asia, adapted to hot, dry climates. It is thought to be the progenitor of the mod Arabian horse and Akhal-Teke.[13]

Only two never-domesticated "wild" groups survived into historic times, Przewalski's horse (Equus ferus przewalski), and the Tarpan (Equus ferus ferus).[xvi] The Tarpan became extinct in the late 19th century and Przewalski'south horse is endangered; it became extinct in the wild during the 1960s, but was re-introduced in the late 1980s to two preserves in Mongolia. Although researchers such as Marija Gimbutas theorized that the horses of the Chalcolithic period were Przewalski's, more recent genetic studies bespeak that Przewalski'south horse is non an ancestor to modern domesticated horses.[12] Other now-extinct subspecies of Equus ferus appears to have been the stock from which domesticated horses are descended.[16]

Genetic evidence [edit]

The early stages of domestication were marked past a rapid increment in coat color variation.[17]

A 2014 study compared DNA from aboriginal equus caballus bones that predated domestication and compared them to DNA of modern horses, discovering 125 genes that correlated to domestication. Some were physical, affecting muscle and limb development, cardiac forcefulness and balance. Others were linked to cognitive function and most probable were critical to the taming of the horse, including social beliefs, learning capabilities, fear response, and agreeableness.[xviii] The Dna used in this study came from equus caballus bones sixteen,000 to 43,000 years agone, and therefore the precise changes that occurred at the time of domestication have even so to be sequenced.[nineteen]

The domestication of stallions and mares can exist analyzed separately by looking at those portions of the DNA that are passed on exclusively along the maternal (mitochondrial Dna or mtDNA) or paternal line (Y-chromosome or Y-DNA). DNA studies indicate that there may accept been multiple domestication events for mares, as the number of female lines required to account for the genetic diversity of the modernistic equus caballus suggests a minimum of 77 different ancestral mares, divided into 17 singled-out lineages.[12] On the other hand, genetic prove with regard to the domestication of stallions points at a single domestication issue for a limited number of stallions combined with repeated restocking of wild females into the domesticated herds.[twenty] [21] [22]

A report published in 2012 that performed genomic sampling on 300 work horses from local areas as well as a review of previous studies of archeology, mitochondrial Dna, and Y-DNA suggested that horses were originally domesticated in the western office of the Eurasian steppe.[23] Both domesticated stallions and mares spread out from this surface area, and then additional wild mares were added from local herds; wild mares were easier to handle than wild stallions. Nigh other parts of the globe were ruled out every bit sites for equus caballus domestication, either due to climate unsuitable for an indigenous wild horse population or no bear witness of domestication.[24]

Genes located on the Y-chromosome are inherited just from sire to its male offspring and these lines show a very reduced caste of genetic variation (aka genetic homogeneity) in modern domestic horses, far less than expected based on the overall genetic variation in the remaining genetic fabric.[20] [21] This indicates that a relatively few stallions were domesticated and that it is unlikely that many male person offspring originating from unions betwixt wild stallions and domestic mares were included in early on domesticated breeding stock.[20] [21]

Genes located in the mitochondrial DNA are passed on along the maternal line from the mother to her offspring. Multiple analyses of the mitochondrial DNA obtained from modern horses as well as from horse bones and teeth from archaeological and palaeological finds consistently shows an increased genetic diversity in the mitochondrial Deoxyribonucleic acid compared to the remaining Deoxyribonucleic acid, showing that a big number of mares has been included into the convenance stock of the originally domesticated horse.[12] [22] [25] [26] [27] [28] Variation in the mitochondrial Deoxyribonucleic acid is used to determine and so-called haplogroups. A haplogroup is a group of closely related haplotypes that share the same common ancestor. In horses, seven main haplogroups are recognized (A-G), each with several subgroups. Several haplogroups are unequally distributed effectually the globe, indicating the addition of local wild mares to the domesticated stock.[12] [22] [26] [27] [28] One of these haplotypes (Lusitano group C) is exclusively found in the Iberian Peninsula, leading to a hypothesis that the Iberian peninsula or North Africa was an contained origin for domestication of the horse.[26] However, until there is additional analysis of nuclear DNA and a better understanding of the genetic construction of the earliest domestic herds, this theory cannot be confirmed or refuted.[26] Information technology remains possible that a 2d, independent, domestication site might exist but, equally of 2012, enquiry has neither confirmed nor disproven that hypothesis.[24]

Even though horse domestication became widespread in a short menstruum of time, it is nevertheless possible that domestication began with a unmarried civilization, which passed on techniques and convenance stock. Information technology is possible that the two "wild" subspecies remained when all other groups of one time-"wild" horses died out because all others had been, perhaps, more than suitable for taming by humans and the selective convenance that gave rise to the modernistic domestic horse.[29]

Archaeological evidence [edit]

Archaeological evidence for the domestication of the equus caballus comes from three kinds of sources: 1) changes in the skeletons and teeth of ancient horses; 2) changes in the geographic distribution of ancient horses, peculiarly the introduction of horses into regions where no wild horses had existed; and 3) archaeological sites containing artifacts, images, or testify of changes in man behavior continued with horses.

Examples include horse remains interred in human graves; changes in the ages and sexes of the horses killed by humans; the appearance of horse corrals; equipment such as bits or other types of horse tack; horses interred with equipment intended for use past horses, such every bit chariots; and depictions of horses used for riding, driving, draught piece of work, or symbols of human ability.

Few of these categories, taken solitary, provide irrefutable evidence of domestication, just the cumulative testify becomes increasingly more persuasive.

Horses interred with chariots [edit]

The least aboriginal, just most persuasive, show of domestication comes from sites where horse leg basic and skulls, probably originally attached to hides, were interred with the remains of chariots in at least 16 graves of the Sintashta and Petrovka cultures. These were located in the steppes southeast of the Ural Mountains, between the upper Ural and upper Tobol Rivers, a region today divided betwixt southern Russia and northern Kazakhstan. Petrovka was a lilliputian later than and probably grew out of Sintashta, and the two complexes together spanned nearly 2100–1700 BCE.[5] [30] A few of these graves contained the remains of every bit many as eight sacrificed horses placed in, above, and beside the grave.

In all of the dated chariot graves, the heads and hooves of a pair of horses were placed in a grave that once contained a chariot. Bear witness of chariots in these graves was inferred from the impressions of two spoked wheels set in grave floors 1.2–1.6m apart; in almost cases the residual of the vehicle left no trace. In addition, a pair of disk-shaped antler "cheekpieces," an ancient predecessor to a modernistic bit shank or bit band, were placed in pairs abreast each horse head-and-hoof sacrifice. The inner faces of the disks had protruding prongs or studs that would have pressed against the horse's lips when the reins were pulled on the contrary side. Studded cheekpieces were a new and fairly severe kind of control device that appeared simultaneously with chariots.

All of the dated chariot graves contained wheel impressions, horse bones, weapons (arrow and javelin points, axes, daggers, or stone mace-heads), human skeletal remains, and cheekpieces. Because they were buried in teams of two with chariots and studded cheekpieces, the evidence is extremely persuasive that these steppe horses of 2100–1700 BCE were domesticated. Shortly after the period of these burials, the expansion of the domestic horse throughout Europe was little short of explosive. In the infinite of possibly 500 years, there is evidence of horse-drawn chariots in Greece, Egypt, and Mesopotamia. By some other 500 years, the horse-fatigued chariot had spread to Red china.

Skeletal indicators of domestication [edit]

Some researchers do not consider an fauna to be "domesticated" until it exhibits physical changes consequent with selective breeding, or at least having been born and raised entirely in captivity. Until that point, they classify captive animals as merely "tamed". Those who agree to this theory of domestication point to a change in skeletal measurements detected among horse basic recovered from middens dated nigh 2500 BCE in eastern Hungary in Bell-Beaker sites, and in later on Bronze Age sites in the Russian steppes, Spain, and Eastern Europe.[6] [31] Horse bones from these contexts exhibited an increase in variability, idea to reflect the survival under human care of both larger and smaller individuals than appeared in the wild; and a decrease in average size, thought to reflect penning and restriction in nutrition. Horse populations that showed this combination of skeletal changes probably were domesticated. Virtually evidence suggests that horses were increasingly controlled by humans after almost 2500 BCE. Notwithstanding, more recently there take been skeletal remains found at a site in Kazakhstan which brandish the smaller, more slender limbs feature of corralled animals, dated to 3500 BCE.[3]

Botai culture [edit]

Some of the almost intriguing prove of early on domestication comes from the Botai civilization, institute in northern Republic of kazakhstan. The Botai culture was a civilization of foragers who seem to have adopted horseback riding in gild to hunt the arable wild horses of northern Kazakhstan between 3500 and 3000 BCE.[32] [33] Botai sites had no cattle or sheep bones; the just domesticated animals, in improver to horses, were dogs. Botai settlements in this menstruation contained between 50 and 150 pit houses. Garbage deposits contained tens to hundreds of thousands of discarded creature basic, 65% to 99% of which had come up from horses. Too, in that location has been evidence institute of horse milking at these sites, with horse milk fats soaked into pottery shards dating to 3500 BCE.[3] Before hunter-gatherers who lived in the same region had non hunted wild horses with such success, and lived for millennia in smaller, more shifting settlements, oft containing less than 200 wild beast bones.

Entire herds of horses were slaughtered by the Botai hunters, patently in hunting drives. The adoption of horseback riding might explain the emergence of specialized horse-hunting techniques and larger, more permanent settlements. Domesticated horses could have been adopted from neighboring herding societies in the steppes west of the Ural Mountains, where the Khvalynsk culture had herds of cattle and sheep, and perhaps had domesticated horses, as early as 4800 BCE.[33]

Other researchers have argued that all of the Botai horses were wild, and that the equus caballus-hunters of Botai hunted wild horses on human foot. As evidence, they note that zoologists have establish no skeletal changes in the Botai horses that indicate domestication. Moreover, considering they were hunted for food, the bulk of the horse remains institute in Botai-culture settlements indeed probably were wild. On the other hand, any domesticated riding horses were probably the same size as their wild cousins and cannot now be distinguished past bone measurements.[six] They too notation that the age construction of the horses slaughtered at Botai represents a natural demographic profile for hunted animals, not the pattern expected if they were domesticated and selected for slaughter.[34] However, these arguments were published before a corral was discovered at Krasnyi Yar and mats of horse-dung at two other Botai sites. A report in 2018 revealed that the Botai horses did not contribute significantly to the genetics of modernistic domesticated horses, and that therefore a subsequent and separate domestication effect must have been responsible for the modern domestic equus caballus.[35]

Bit wear [edit]

The presence of bit vesture is an indicator that a horse was ridden or driven, and the earliest of such evidence from a site in Republic of kazakhstan dates to 3500 BCE.[3] The absence of bit vesture on horse teeth is non conclusive evidence against domestication considering horses can exist ridden and controlled without $.25 by using a noseband or a hackamore, merely such materials practice non produce significant physiological changes nor are they apt to be preserved for millennia.

The regular use of a bit to control a equus caballus can create wear facets or bevels on the anterior corners of the lower second premolars. The corners of the horse'southward mouth normally keep the chip on the "bars" of the oral cavity, an interdental space where at that place are no teeth, forward of the premolars. The chip must be manipulated by a human or the horse must move it with its natural language for it to touch the teeth. Wear tin be acquired by the bit abrading the front corners of the premolars if the horse grasps and releases the bit between its teeth; other wear tin be created by the flake hit the vertical front edge of the lower premolars,[36] [37] due to very stiff force per unit area from a human handler.

Modern experiments showed that fifty-fifty organic bits of rope or leather tin create pregnant wear facets, and also showed that facets 3mm (.118 in) deep or more practise not appear on the premolars of wild horses.[38] However, other researchers disputed both conclusions.[34]

Article of clothing facets of three mm or more were found on 7 horse premolars in two sites of the Botai culture, Botai and Kozhai ane, dated about 3500–3000 BCE.[33] [39] The Botai culture premolars are the earliest reported multiple examples of this dental pathology in any archaeological site, and preceded any skeletal change indicators past 1,000 years. While wear facets more than 3 mm deep were discovered on the lower 2nd premolars of a single stallion from Dereivka in Ukraine, an Eneolithic settlement dated near 4000 BCE,[39] dental textile from one of the worn teeth after produced a radiocarbon appointment of 700–200 BCE, indicating that this stallion was actually deposited in a pit dug into the older Eneolithic site during the Fe Age.[33]

Dung and corrals [edit]

Soil scientists working with Sandra Olsen of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History at the Chalcolithic (too chosen Eneolithic, or "Copper Age") settlements of Botai and Krasnyi Yar in northern Kazakhstan plant layers of horse dung, discarded in unused house pits in both settlements.[forty] The collection and disposal of equus caballus dung suggests that horses were confined in corrals or stables. An actual corral, dated to 3500–3000 BCE was identified at Krasnyi Yar past a pattern of post holes for a round fence, with the soils within the fence yielding 10 times more phosphorus than the soils outside. The phosphorus could correspond the remains of manure.[41]

Geographic expansion [edit]

The advent of horse remains in human settlements in regions where they had not previously been present is another indicator of domestication. Although images of horses appear every bit early as the Upper Paleolithic flow in places such equally the caves of Lascaux, French republic, suggesting that wild horses lived in regions exterior of the Eurasian steppes before domestication and may have even been hunted by early humans, concentration of remains suggests animals existence deliberately captured and contained, an indicator of domestication, at least for food, if non necessarily use as a working animate being.

Effectually 3500–3000 BCE, horse bones began to appear more oft in archaeological sites beyond their centre of distribution in the Eurasian steppes and were seen in central Europe, the eye and lower Danube valley, and the North Caucasus and Transcaucasia. Evidence of horses in these areas had been rare before, and as numbers increased, larger animals likewise began to appear in equus caballus remains. This expansion in range was contemporary with the Botai culture, where there are indications that horses were corralled and ridden. This does not necessarily mean that horses were first domesticated in the steppes, but the horse-hunters of the steppes certainly pursued wild horses more than than in whatsoever other region. This geographic expansion is interpreted past many zoologists every bit an early on phase in the spread of domesticated horses.[31] [42] [43]

European wild horses were hunted for up to ten% of the animal bones in a handful of Mesolithic and Neolithic settlements scattered across Spain, France, and the marshlands of northern Frg, simply in many other parts of Europe, including Greece, the Balkans, the British Isles, and much of central Europe, horse bones exercise not occur or occur very rarely in Mesolithic, Neolithic or Chalcolithic sites. In contrast, wild horse bones regularly exceeded forty% of the identified creature bones in Mesolithic and Neolithic camps in the Eurasian steppes, west of the Ural Mountains.[42] [44] [45]

Horse basic were rare or absent-minded in Neolithic and Chalcolithic kitchen garbage in western Turkey, Mesopotamia, nearly of Iran, South and Central Asia, and much of Europe.[42] [43] [46] While equus caballus bones have been identified in Neolithic sites in key Turkey, all equids together totaled less than 3% of the beast bones. Within this three percentage, horses were less than 10%, with 90% or more of the equids represented by onagers (Equus hemionus) or some other ass-similar equid that afterward became extinct, Equus hydruntinus.[47] Onagers were the most common native wild equids of the Nigh East. They were hunted in Syria, Anatolia, Mesopotamia, Iran, and Primal Asia; and domesticated asses (Equus asinus) were imported into Mesopotamia, probably from Egypt, but wild horses manifestly did non live there.[48]

Other evidence of geographic expansion [edit]

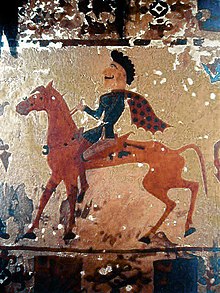

In Northern Caucasus, the Maikop culture settlements and burials of c. 3300 BC contain both equus caballus bones and images of horses. A frieze of nineteen horses painted in black and carmine colors is found in one of the Maikop graves. The widespread appearance of horse bones and images in Maikop sites propose to some observers that horseback riding began in the Maikop period.[49]

Later, images of horses, identified by their short ears, flowing manes, and tails that bushed out at the dock, began to appear in artistic media in Mesopotamia during the Akkadian flow, 2300–2100 BCE. The discussion for "horse", literally translated as ass of the mountains, kickoff appeared in Sumerian documents during the Third dynasty of Ur, near 2100–2000 BCE.[48] [50] The kings of the Third Dynasty of Ur apparently fed horses to lions for royal entertainment, perhaps indicating that horses were even so regarded every bit more than exotic than useful, but King Shulgi, well-nigh 2050 BCE, compared himself to "a horse of the highway that swishes its tail", and i image from his reign showed a human being apparently riding a equus caballus at total gallop.[51] Horses were imported into Mesopotamia and the lowland Near East in larger numbers afterwards 2000 BCE in connection with the beginning of chariot warfare.

A further expansion, into the lowland Near Eastward and northwestern China, likewise happened around 2000 BCE, again plainly in conjunction with the chariot. Although Equus bones of uncertain species are establish in some Late Neolithic sites in People's republic of china dated before 2000 BCE, Equus caballus or Equus ferus bones outset appeared in multiple sites and in significant numbers in sites of the Qijia and Siba cultures, 2000–1600 BCE, in Gansu and the northwestern provinces of China.[52] The Qijia culture was in contact with cultures of the Eurasian steppes, every bit shown through similarities betwixt Qijia and Late Bronze Age steppe metallurgy, and then it was probably through these contacts that domesticated horses first became frequent in northwestern China.[ citation needed ]

In 2008, archaeologists announced the discovery of rock fine art in Somalia'south northern Dhambalin region, which the researchers suggest is i of the earliest known depictions of a hunter on horseback. The rock art is in the Ethiopian-Arabian way, dated to chiliad to 3000 BCE.[53] [54]

Horse images as symbols of ability [edit]

Well-nigh 4200-4000 BCE, more than 500 years earlier the geographic expansion evidenced by the presence of horse bones, new kinds of graves, named after a grave at Suvorovo, appeared north of the Danube delta in the coastal steppes of Ukraine about Izmail. Suvorovo graves were like to and probably derived from earlier funeral traditions in the steppes effectually the Dnieper River. Some Suvorovo graves contained polished rock mace-heads shaped like horse heads and horse tooth chaplet.[55] Before steppe graves also had contained polished stone mace-heads, some of them carved in the shape of animal heads.[56] Settlements in the steppes gimmicky with Suvorovo, such as Sredni Stog II and Dereivka on the Dnieper River, independent 12–52% horse bones.[57]

When Suvorovo graves appeared in the Danube delta grasslands, horse-head maces also appeared in some of the indigenous farming towns of the Trypillia and Gumelnitsa cultures in nowadays-mean solar day Romania and Moldova, near the Suvorovo graves.[58] These agricultural cultures had not previously used polished-rock maces, and horse bones were rare or absent in their settlement sites. Probably their horse-caput maces came from the Suvorovo immigrants. The Suvorovo people in turn acquired many copper ornaments from the Trypillia and Gumelnitsa towns. Later on this episode of contact and trade, but nevertheless during the catamenia 4200–4000 BCE, most 600 agricultural towns in the Balkans and the lower Danube valley, some of which had been occupied for 2000 years, were abandoned.[59] Copper mining ceased in the Balkan copper mines,[60] and the cultural traditions associated with the agricultural towns were terminated in the Balkans and the lower Danube valley. This collapse of "Old Europe" has been attributed to the immigration of mounted Indo-European warriors.[61] The collapse could take been caused by intensified warfare, for which there is some evidence; and warfare could have been worsened by mounted raiding; and the horse-head maces have been interpreted as indicating the introduction of domesticated horses and riding just earlier the collapse.

Even so, mounted raiding is just 1 possible explanation for this complex event. Environmental deterioration, ecological degradation from millennia of farming, and the burnout of easily mined oxide copper ores also are cited as causal factors.[5] [59]

Artifacts [edit]

Perforated antler objects discovered at Dereivka and other sites contemporary with Suvorovo have been identified as cheekpieces or psalia for horse bits.[56] This identification is no longer widely accepted, as the objects in question accept not been found associated with equus caballus bones, and could have had a diverseness of other functions.[62] Yet, through studies of microscopic wearable, it has been established that many of the bone tools at Botai were used to smooth rawhide thongs, and rawhide thongs might have been used to manufacture of rawhide cords and ropes, useful for horse tack.[32] Similar os thong-smoothers are known from many other steppe settlements, but information technology cannot be known how the thongs were used. The oldest artifacts clearly identified as horse tack—bits, bridles, cheekpieces, or any other kind of horse gear—are the antler disk-shaped cheekpieces associated with the invention of the chariot, at the Sintashta-Petrovka sites.

Horses interred in human graves [edit]

The oldest possible archaeological indicator of a inverse relationship between horses and humans is the advent about 4800–4400 BCE of horse bones and carved images of horses in Chalcolithic graves of the early on Khvalynsk culture and the Samara culture in the middle Volga region of Russia. At the Khvalynsk cemetery near the town of Khvalynsk, 158 graves of this period were excavated. Of these, 26 graves contained parts of sacrificed domestic animals, and additional sacrifices occurred in ritual deposits on the original ground surface above the graves. Ten graves contained parts of lower equus caballus legs; 2 of these also contained the bones of domesticated cattle and sheep. At least 52 domesticated sheep or goats, 23 domesticated cattle, and eleven horses were sacrificed at Khvalynsk. The inclusion of horses with cattle and sheep and the exclusion of plainly wild fauna together suggest that horses were categorized symbolically with domesticated animals.[ citation needed ]

At S'yezzhe, a gimmicky cemetery of the Samara civilization, parts of two horses were placed above a group of human graves. The pair of horses here was represented by the caput and hooves, probably originally fastened to hides. The same ritual—using the hide with the caput and lower leg bones equally a symbol for the whole brute—was used for many domesticated cattle and sheep sacrifices at Khvalynsk. Horse images carved from bone were placed in the above-ground ochre deposit at S'yezzhe and occurred at several other sites of the same period in the centre and lower Volga region. Together these archaeological clues advise that horses had a symbolic importance in the Khvalynsk and Samara cultures that they had lacked before, and that they were associated with humans, domesticated cattle, and domesticated sheep. Thus, the earliest phase in the domestication of the horse might have begun during the period 4800-4400 BCE.[ citation needed ]

Methods of domestication [edit]

Equidae died out in the Western Hemisphere at the end of the terminal glacial period. A question raised is why and how horses avoided this fate on the Eurasian continent. Information technology has been theorized that domestication saved the species.[63] While the environmental conditions for equine survival in Europe were somewhat more favorable in Eurasia than in the Americas, the same stressors that led to extinction for the Mammoth had an upshot upon horse populations. Thus, some time later 8000 BCE, the approximate engagement of extinction in the Americas, humans in Eurasia may have begun to continue horses as a livestock food source, and by keeping them in captivity, may have helped to preserve the species.[63] Horses also fit the six core criteria for livestock domestication, and thus, it could be argued, "chose" to live in close proximity to humans.[29]

One model of equus caballus domestication starts with individual foals existence kept as pets while the adult horses were slaughtered for meat. Foals are relatively pocket-sized and easy to handle. Horses behave every bit herd animals and need companionship to thrive. Both historic and modernistic information shows that foals can and will bail to humans and other domestic animals to come across their social needs. Thus domestication may have started with young horses being repeatedly made into pets over fourth dimension, preceding the great discovery that these pets could be ridden or otherwise put to work.

However, there is disagreement over the definition of the term domestication. Ane interpretation of domestication is that information technology must include physiological changes associated with existence selectively bred in captivity, and not merely "tamed." It has been noted that traditional peoples worldwide (both hunter-gatherers and horticulturists) routinely tame individuals from wild species, typically by paw-rearing infants whose parents have been killed, and these animals are not necessarily "domesticated."[ citation needed ]

On the other hand, some researchers look to examples from historical times to hypothesize how domestication occurred. For example, while Native American cultures captured and rode horses from the 16th century onwards, most tribes did not exert meaning command over their breeding, thus their horses developed a genotype and phenotype adjusted to the uses and climatological conditions in which they were kept, making them more than of a landrace than a planned breed as defined by modern standards, but nonetheless "domesticated".[ citation needed ]

Driving versus riding [edit]

A difficult question is if domesticated horses were first ridden or driven. While the well-nigh unequivocal show shows horses first being used to pull chariots in warfare, in that location is strong, though indirect, evidence for riding occurring first, specially by the Botai. Flake wear may correlate to riding, though, equally the modern hackamore demonstrates, horses tin be ridden without a fleck by using rope and other evanescent materials to make equipment that fastens around the nose. Then the absence of unequivocal show of early on riding in the tape does not settle the question.

Thus, on one paw, logic suggests that horses would have been ridden long before they were driven. But information technology is also far more difficult to get together testify of this, as the materials required for riding—simple hackamores or blankets—would not survive as artifacts, and other than tooth wear from a flake, the skeletal changes in an animal that was ridden would not necessarily be particularly noticeable. Direct evidence of horses existence driven is much stronger.[64]

On the other hand, others argue that testify of flake wear does non necessarily correlate to riding. Some theorists speculate that a horse could accept been controlled from the basis past placing a bit in the mouth, connected to a pb rope, and leading the beast while pulling a primitive wagon or plough. Since oxen were ordinarily relegated to this duty in Mesopotamia, it is possible that early on plows might accept been attempted with the horse, and a bit may indeed have been significant every bit part of agrarian development rather than as warfare technology.

Horses in celebrated warfare [edit]

While riding may have been practiced during the quaternary and 3rd millennia BCE, and the disappearance of "Onetime European" settlements may exist related to attacks by horseback-mounted warriors, the clearest influence by horses on ancient warfare was by pulling chariots, introduced around 2000 BCE.

Horses in the Statuary Age were relatively modest by modern standards, which led some theorists to believe the aboriginal horses were likewise small to be ridden so must have been used for driving. Herodotus' description of the Sigynnae, a steppe people who bred horses too small to ride simply extremely efficient at drawing chariots, illustrates this stage. Yet, as horses remained generally smaller than modern equines well into the Middle Ages,[65] this theory is highly questionable.

The Iron Age in Mesopotamia saw the ascension of mounted cavalry equally a tool of war, equally evidenced by the notable successes of mounted archer tactics used by various invading equestrian nomads such as the Parthians. Over fourth dimension, the chariot gradually became obsolete.

The horse of the Iron Historic period was withal relatively small, maybe 12.2 to fourteen.ii easily (fifty to 58 inches, 127 to 147 cm) high (measured at the withers.) This was shorter overall than the boilerplate elevation of modern riding horses, which range from about 14.2 to 17.2 hands (58 to 70 inches, 147 to 178 cm). However, minor horses were used successfully as light cavalry for many centuries. For instance, Savage ponies, believed to be descended from Roman cavalry horses, are comfortably able to carry fully grown adults (although with rather limited ground clearance) at an average summit of 13.2 hands (54 inches, 137 cm) Besides, the Arabian horse is noted for a short back and dense bone, and the successes of the Muslims against the heavy mounted knights of Europe demonstrated that a equus caballus standing 14.ii easily (58 inches, 147 cm) can easily carry a total-grown homo adult into battle.

Mounted warriors such equally the Scythians, Huns and Vandals of late Roman antiquity, the Mongols who invaded eastern Europe in the 7th century through 14th centuries CE, the Arab warriors of the 7th through 14th centuries CE, and the Native Americans in the 16th through 19th centuries each demonstrated effective forms of light cavalry.

Encounter also [edit]

- Anthrozoology

- Equestrian nomad

- Listing of horse breeds

References [edit]

- ^ Matossian, Mary Kilbourne (2016). Shaping Earth History. Routledge. p. 43. ISBN978-1-315-50348-6.

- ^ "What We Theorize – When and Where Domestication Occurred". International Museum of the Horse. Archived from the original on 19 July 2016. Retrieved 27 Jan 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Horsey-aeology, Binary Black Holes, Tracking Crimson Tides, Fish Re-evolution, Walk Like a Man, Fact or Fiction". Quirks and Quarks Podcast with Bob Macdonald. CBC Radio. vii March 2009.

- ^ Outram, Alan K.; et al. (2009). "The Primeval Horse Harnessing and Milking". Science. 323 (5919): 1332–1335. Bibcode:2009Sci...323.1332O. doi:ten.1126/science.1168594. PMID 19265018. S2CID 5126719.

- ^ a b c Anthony, David W. (2007). The Horse, the Wheel, and Linguistic communication: How Bronze Historic period Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN978-0-691-05887-0.

- ^ a b c Benecke, Norbert; Von den Dreisch, Angela (2003). "Horse exploitation in the Kazakh steppes during the Eneolithic and Bronze Age". In Levine, Marsha; Renfrew, Colin; Boyle, Katie (eds.). Prehistoric Steppe Adaptation and the Equus caballus. Cambridge: McDonald Establish. pp. 69–82. ISBN978-1-902937-09-0.

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in Red china; Volume 4, Physics and Concrete Technology, Part 2, Mechanical Engineering. Taipei: Caves Books.

- ^ Clutton-Brock, Juliet (1992). Horse Power: A History of the Equus caballus and the Donkey in Human Societies. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 138. ISBN978-0-674-40646-9.

- ^ a b c d Weinstock, J.; et al. (2005). "Development, systematics, and phylogeography of Pleistocene horses in the New World: a molecular perspective". PLOS Biological science. 3 (8): e241. doi:ten.1371/journal.pbio.0030241. PMC1159165. PMID 15974804.

- ^ Luís, Cristina; et al. (2006). "Iberian Origins of New World Equus caballus Breeds". Journal of Heredity. 97 (2): 107–113. doi:x.1093/jhered/esj020. PMID 16489143.

- ^ Buck, Caitlin E.; Bard, Edouard (2007). "A calendar chronology for Pleistocene mammoth and horse extinction in North America based on Bayesian radiocarbon calibration". 4th Science Reviews. 26 (17–eighteen): 2031–2035. Bibcode:2007QSRv...26.2031B. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2007.06.013.

- ^ a b c d eastward f Jansen, Thomas; et al. (2002). "Mitochondrial Dna and the origins of the domestic horse". Proceedings of the National University of Sciences. 99 (xvi): 10905–10910. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9910905J. doi:ten.1073/pnas.152330099. PMC125071. PMID 12130666.

- ^ a b c d Bennett, Deb (1998). Conquerors: The Roots of New World Horsemanship (1st ed.). Solvang, CA: Amigo Publications. ISBN978-0-9658533-0-9.

- ^ Olsen, Sandra L. (1996). "Horse Hunters of the Ice Age". Horses Through Time . Bedrock, CO: Roberts Rinehart Publishers. ISBN978-ane-57098-060-two.

- ^ MacPhee, Ross D. E. (ed.) (1999). MacPhee, Ross D. East (ed.). Extinctions in Near Time: Causes, Contexts, and Consequences. New York: Kluwer Printing. doi:10.1007/978-one-4757-5202-1. ISBN978-0-306-46092-0. S2CID 21839980.

- ^ a b Groves, Colin (1986). "The taxonomy, distribution, and adaptations of recent Equids". In Meadow, Richard H.; Uerpmann, Hans-Peter (eds.). Equids in the Ancient Globe. Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients: Reihe A (Naturwissenschaften). Vol. xix. Wiesbaden: Ludwig Reichert Verlag. pp. 11–65.

- ^ Wutke S, Benecke Northward, Sandoval-Castellanos E, Döhle H, et al. (7 December 2016). "Spotted phenotypes in horses lost bewitchery in the Middle Ages". Scientific Reports. 6: 38548. Bibcode:2016NatSR...638548W. doi:10.1038/srep38548. PMC5141471. PMID 27924839.

- ^ Schubert, Mikkel; Jónsson, Hákon; Chang, Dan; Der Sarkissian, Clio; Ermini, Luca; Ginolhac, Aurélien; Albrechtsen, Anders; Dupanloup, Isabelle; Foucal, Adrien; Petersen, Bent; Fumagalli, Matteo; Raghavan, Maanasa; Seguin-Orlando, Andaine; Korneliussen, Thorfinn S.; Velazquez, Amhed M. 5.; Stenderup, Jesper; Hoover, Cindi A.; Rubin, Carl-Johan; Alfarhan, Ahmed H.; Alquraishi, Saleh A.; Al-Rasheid, Khaled A. S.; MacHugh, David E.; Kalbfleisch, Ted; MacLeod, James N.; Rubin, Edward M.; Sicheritz-Ponten, Thomas; Andersson, Leif; Hofreiter, Michael; Marques-Bonet, Tomas; Gilbert, Chiliad. Thomas P.; Nielsen, Rasmus; Excoffier, Laurent; Willerslev, Eske; Shapiro, Beth; Orlando, Ludovic (2014). "Prehistoric genomes reveal the genetic foundation and cost of horse domestication". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (52): E5661–E5669. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111E5661S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1416991111. PMC4284583. PMID 25512547.

- ^ Begley, Sharon (16 December 2014). "How did we domesticate horses? Genetic written report yields new evidence". Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ a b c Lau, A. N.; Peng, L.; Goto, H.; Chemnick, L.; Ryder, O. A.; Makova, K. D. (2009). "Horse Domestication and Conservation Genetics of Przewalski'south Equus caballus Inferred from Sex Chromosomal and Autosomal Sequences". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 26 (1): 199–208. doi:10.1093/molbev/msn239. PMID 18931383.

- ^ a b c Lindgren, Gabriella; Niclas Backström; June Swinburne; Linda Hellborg; Annika Einarsson; Kaj Sandberg; Gus Cothran; Carles Vilà; Matthew Binns; Hans Ellegren (2004). "Express number of patrilines in horse domestication". Nature Genetics. 36 (4): 335–336. doi:10.1038/ng1326. PMID 15034578.

- ^ a b c Vilà, C.; et al. (2001). "Widespread origins of domestic horse lineages". Science. 291 (5503): 474–477. Bibcode:2001Sci...291..474V. doi:10.1126/science.291.5503.474. PMID 11161199.

- ^ Warmuth, Vera; Eriksson, Anders; Ann Bower, Mim; Barker, Graeme; Barrett, Elizabeth; Kent Hanks, Bryan; Li, Shuicheng; Lomitashvili, David; Ochir-Goryaeva, Maria; Sizonov, Grigory 5.; Soyonov, Vasiliy; Manica, Andrea (2012). "Reconstructing the origin and spread of horse domestication in the Eurasian steppe". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (21): 8202–8206. doi:x.1073/pnas.1111122109. PMC3361400. PMID 22566639.

- ^ a b Lesté-Lasserre,Christa. Researchers: Horses Start Domesticated in Western Steppes, The Horse 13 June 2012, Article # 20162

- ^ Cozzi, Chiliad. C., Strillacci, Grand. G., Valiati, P., Bighignoli, B., Cancedda, M. & Zanotti, Yard. (2004). "Mitochondrial D-loop sequence variation among Italian horse breeds". Genetics Option Development. 36 (half dozen): 663–672. doi:10.1051/gse:2004023. PMC2697199. PMID 15496286.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors listing (link) - ^ a b c d Lira, Jaime; et al. (2010). "Ancient Deoxyribonucleic acid reveals traces of Iberian Neolithic and Bronze Age lineages in mod Iberian horses" (PDF). Molecular Ecology. 19 (i): 64–78. doi:ten.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04430.x. PMID 19943892. S2CID 1376591.

- ^ a b Priskin, K.; Szabo, Grand.; Tomory, Thou.; Bogacsi-Szabo, E.; Csanyi, B.; Eordogh, R.; Downes, C. South.; Rasko, I. (2010). "Mitochondrial sequence variation in ancient horses from the Carpathian Basin and possible mod relatives". Genetica. 138 (ii): 211–218. doi:ten.1007/s10709-009-9411-x. PMID 19789983. S2CID 578727.

- ^ a b Cai, D. West.; Tang, Z. W.; Han, 50.; Speller, C. F.; Yang, D. Y. Y.; Ma, Ten. 50.; Cao, J. Due east.; Zhu, H.; Zhou, H. (2009). "Ancient DNA provides new insights into the origin of the Chinese domestic horse" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science. 36 (3): 835–842. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2008.11.006.

- ^ a b Diamond, Jared (1997). Guns, Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human being Societies. New York: Due west. W. Norton. ISBN978-0-393-03891-0.

- ^ Kuznetsov, P. F. (2006). "The emergence of Bronze Age chariots in eastern Europe". Antiquity. 80 (309): 638–645. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00094096. S2CID 162580424. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012.

- ^ a b Bökönyi, Sándor (1978). "The earliest waves of domestic horses in due east Europe". Journal of Indo-European Studies. 6 (1/ii): 17–76.

- ^ a b Olsen, Sandra 50. (2003). "The exploitation of horses at Botai, Kazakhstan". In Levine, Marsha; Renfrew, Colin; Boyle, Katie (eds.). Prehistoric Steppe Adaptation and the Horse. Cambridge: McDonald Institute. pp. 83–104. ISBN978-i-902937-09-0.

- ^ a b c d Anthony, David W.; Brown, Dorcas (2000). "Eneolithic equus caballus exploitation in the Eurasian steppes: diet, ritual and riding". Antiquity. 74 (283): 75–86. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00066163. S2CID 163782751.

- ^ a b Levine, Marsha A. (1999). "The Origins of Horse Husbandry on the Eurasian Steppe". In Levine, Marsha; Rassamakin, Yuri; Kislenko, Aleksandr; Tatarintseva, Nataliya (eds.). Belatedly Prehistoric Exploitation of the Eurasian Steppe. Cambridge: McDonald Found Monographs. pp. five–58. ISBN978-i-902937-03-8.

- ^ New research shows how Indo-European languages spread across Asia. Scientific discipline Daily.

- ^ Brown, Dorcas; Anthony, David W. (1998). "Bit Wearable, Horseback Riding and the Botai site in Kazakstan". Journal of Archaeological Science. 25 (4): 331–347. doi:ten.1006/jasc.1997.0242.

- ^ Bendry, Robin (2007). "New methods for the identification of bear witness for bitting on horse remains from archaeological sites". Journal of Archaeological Science. 34 (7): 1036–1050. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2006.09.010.

- ^ Anthony, David Westward.; Brown, Dorcas R.; George, Christian (2006). "Early on horseback riding and warfare: the importance of the magpie effectually the neck". In Olsen, Sandra Fifty.; Grant, Susan; Choyke, Alice; Bartosiewicz, Laszlo (eds.). Horses and Humans: The Evolution of the Equine-Human relationship. British Archaeological Reports International Serial. Vol. 1560. Oxford: Archaeopress. pp. 137–156. ISBN978-1-84171-990-0.

- ^ a b Anthony, David W.; Telegin, Dimitri; Brown, Dorcas (1991). "The origin of horseback riding". Scientific American. 265 (6): 94–100. Bibcode:1991SciAm.265f..94A. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1291-94.

- ^ French, Charly; Kousoulakou, Maria (2003). "Geomorphological and micromorphological investigations of paleosols, valley sediments, and a sunken-floored habitation at Botai, Kazakstan". In Levine, Marsha; Renfrew, Colin; Boyle, Katie (eds.). Prehistoric Steppe Adaptation and the Equus caballus. Cambridge: McDonald Institute. pp. 105–114. ISBN978-1-902937-09-0.

- ^ Olsen, Sandra L. (23 October 2006). Geochemical evidence of possible horse domestication at the Copper Age Botai settlement of Krasnyi Yar, Kazakhstan. Geological Guild of America Almanac Meeting.

- ^ a b c Benecke, Norbert (1994). Archäozoologische Studien zur Entwicklung der Haustierhaltung in Mitteleuropa und Südskandinavien von Anfängen bis zum ausgehenden Mittelalter. Schriften zur Ur– und Frühgeschichte. Vol. 46. Berlin: Akademie Verlag. ISBN978-3-05-002415-8.

- ^ a b Bökönyi, Sándor (1991). "Tardily Chalcolithic horses in Anatolia". In Meadow, Richard H.; Uerpmann, Hans-Peter (eds.). Equids in the Ancient Earth. Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients: Reihe A (Naturwissenschaften). Vol. 19. Wiesbaden: Ludwig Reichert Verlag. pp. 123–131.

- ^ Benecke, Norbert (1997). "Archaeozoological studies on the transition from the Mesolithic to the Neolithic in the N Pontic region" (PDF). Anthropozoologica. 25–26: 631–641.

- ^ Uerpmann, Hans-Peter (1990). "Die Domestikation des Pferdes im Chalcolithikum West– und Mitteleuropas". Madrider Mitteilungen. 31: 109–153.

- ^ Meadow, Richard H.; Patel, Ajita (1997). "A annotate on 'Horse Remains from Surkotada' by Sándor Bökönyi". South Asian Studies. 13: 308–315. doi:10.1080/02666030.1997.9628545.

- ^ Russell, Nerissa; Martin, Louise (2005). "Çatalhöyük Mammal Remains". In Hodder, Ian (ed.). Inhabiting Çatalhöyük: Reports From the 1995–1999 Seasons. Vol. iv. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Inquiry. pp. 33–98.

- ^ a b Oates, Joan (2003). "A note on the early on evidence for horse and the riding of equids in Southwest asia". In Levine, Marsha; Renfrew, Colin; Boyle, Katie (eds.). Prehistoric Steppe Adaptation and the Horse. Cambridge: McDonald Institute. pp. 115–125. ISBN978-1-902937-09-0.

- ^ David Due west. Anthony, The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton University Press, 2010 ISBN 1400831105 p291

- ^ Drews, Robert (2004). Early Riders: The beginnings of mounted warfare in Asia and Europe. London: Routledge. ISBN978-0-415-32624-seven.

- ^ Owen, David I. (1991). "The first equestrian: an Ur III glyptic scene". Acta Sumerologica. 13: 259–273.

- ^ Linduff, Katheryn One thousand. (2003). "A walk on the wild side: late Shang appropriation of horses in China". In Levine, Marsha; Renfrew, Colin; Boyle, Katie (eds.). Prehistoric Steppe Adaptation and the Horse. Cambridge: McDonald Found. pp. 139–162. ISBN978-1-902937-09-0.

- ^ Mire, Sada (2008). "The Discovery of Dhambalin Rock Fine art Site, Somaliland". African Archaeological Review. 25 (three–4): 153–168. doi:ten.1007/s10437-008-9032-2. S2CID 162960112. Archived from the original on 27 June 2013.

- ^ Alberge, Dalya (17 September 2010). "UK archaeologist finds cave paintings at 100 new African sites". The Guardian.

- ^ Dergachev, Valentin (1999). "Cultural-historical dialogue between the Balkans and Eastern Europe, Neolithic-Bronze Age". Thraco-Dacica (București). 20 (1–two): 33–78.

- ^ a b Kuzmina, E. E. (2003). "Origins of pastoralism in the Eurasian steppes". In Levine, Marsha; Renfrew, Colin; Boyle, Katie (eds.). Prehistoric Steppe Accommodation and the Equus caballus. Cambridge: McDonald Institute. pp. 203–232. ISBN978-ane-902937-09-0.

- ^ Telegin, Dmitriy Yakolevich (1986). Dereivka: a Settlement and Cemetery of Copper Age Horse Keepers on the Middle Dnieper. British Archaeological Reports International Series. Vol. 287. Oxford: BAR. ISBN978-0-86054-369-5.

- ^ Dergachev, Valentin A. (2002). "Ii studies in defense of the migration concept". In Boyle, Katie; Renfrew, Colin; Levine, Marsha (eds.). Ancient Interactions: Eastward and West in Eurasia. Cambridge: McDonald Institute Monographs. pp. 93–112. ISBN978-ane-902937-19-9.

- ^ a b Todorova, Henrietta (1995). "The Neolithic, Eneolithic, and Transitional in Bulgarian Prehistory". In Bailey, Douglass W.; Panayotov, Ivan (eds.). Prehistoric Bulgaria. Monographs in World Archæology. Vol. 22. Madison, WI: Prehistoric Press. pp. 79–98. ISBN978-ane-881094-11-one.

- ^ Pernicka, Ernst (1997). "Prehistoric copper in Republic of bulgaria". Eurasia Antiqua. 3: 41–179.

- ^ Gimbutas, Marija (1991). The Civilisation of the Goddess . San Francisco: Harper. ISBN978-0-06-250368-8.

- ^ Dietz, Ute Luise (1992). "Zur Frage vorbronzezeitlicher Trensenbelege in Europa". Germania. 70 (1): 17–36.

- ^ a b Budiansky, Stephen (1997). The Nature of Horses . New York: Free Printing. ISBN978-0-684-82768-1.

- ^ "Early Attempts at Riding: The Soft Bit and Bridle". Archived from the original on 30 October 2007. Retrieved 26 October 2007.

- ^ Gravett, Christopher (2002). English Medieval Knight 1300–1400. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN978-1-84176-145-9.

Further reading [edit]

- Librado, P., Khan, North., Fages, A. et al. "The origins and spread of domestic horses from the Western Eurasian steppes". In: Nature (2021). https://doi.org/ten.1038/s41586-021-04018-9

External links [edit]

- "The Horse, the Bicycle and Language, How Bronze-Historic period Riders from the Eurasian Steppes shaped the Mod World", David W Anthony, 2007

- The Institute for Aboriginal Equestrian Studies (IAES)

- The Equine Genetics and Evolution Enquiry Information Network

- Horses may first have been domesticated in Republic of kazakhstan

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domestication_of_the_horse

0 Response to "What if the World Had to Use Horses Again"

Post a Comment